Only when it is exceptionally ice cold

It is at a temperature of −70 °C that water molecules at the surface of ice make the most bonds with each other. AMOLF researchers, together with an international team of colleagues, describe this in an article in Physical Review Letters published on September 28. Insights into the behavior of the top layer of ice is important for understanding how glaciers move, how avalanches arise, and why we can skate on ice, among other things.

Water is a strange substance: it expands when it freezes. As the solid form of water (ice) has a lower density than the liquid variant, ice floats on water. This means that you can skate on a lake during a harsh winter while the fish underneath you continue to swim. This unusual property is caused by the molecular structure of water. A water molecule consists of one oxygen atom with two hydrogen atoms. Hydrogen atoms happily form a strong bond with an oxygen atom from another water molecule: we call this a hydrogen bond.

Each oxygen atom can bond to at most four hydrogen atoms: two from its own water molecule, and two from nearby molecules. That can happen in the center of a lump of deeply frozen ice, in which the water molecules assume a crystalline structure that looks like a collection of regular hexagons. This crystal structure takes up quite a lot of space, and that is what makes the density of ice low.

However, the water molecules at the surface of ice have a problem. These water molecules do not lie at an interface with other water molecules but with air, so they cannot utilize their bonding possibilities to the fullest.

Maximum number of bonds

AMOLF researcher Wilbert Smit and AMOLF group leader Huib Bakker studied how the structure of the outermost layer of ice changes as a consequence of the temperature. They found that at an ambient temperature of about −70°C, the water molecules at the ice surface form a maximum number of hydrogen bonds. The researchers also found an explanation for this.

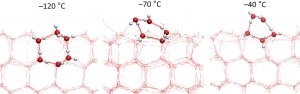

“If it is much colder than −70°C, then the outermost layer of the ice has the same structure as the regular hexagons beneath it, but neatly cut in half. You can compare the structure to a semi-built house where the rods of the reinforced concrete are still sticking up out of the walls of the first floor”, says Wilbert Smit.

As the temperature rises, the ice surface becomes less structured due to the water molecules acquiring more kinetic energy. As a result of this, they rearrange themselves in such a way that the number of bonds between the water molecules initially increases. This rearrangement yields a highest density of hydrogen bonds at a temperature of −70°C.

At temperatures above −70°C, the number of bonds between the molecules decreases again: the top layer increasingly behaves more as water and less as ice. This means, for example, that the surface of the ice we skate on is not actually ice but a layer of water.

Simulations and sensitive technique

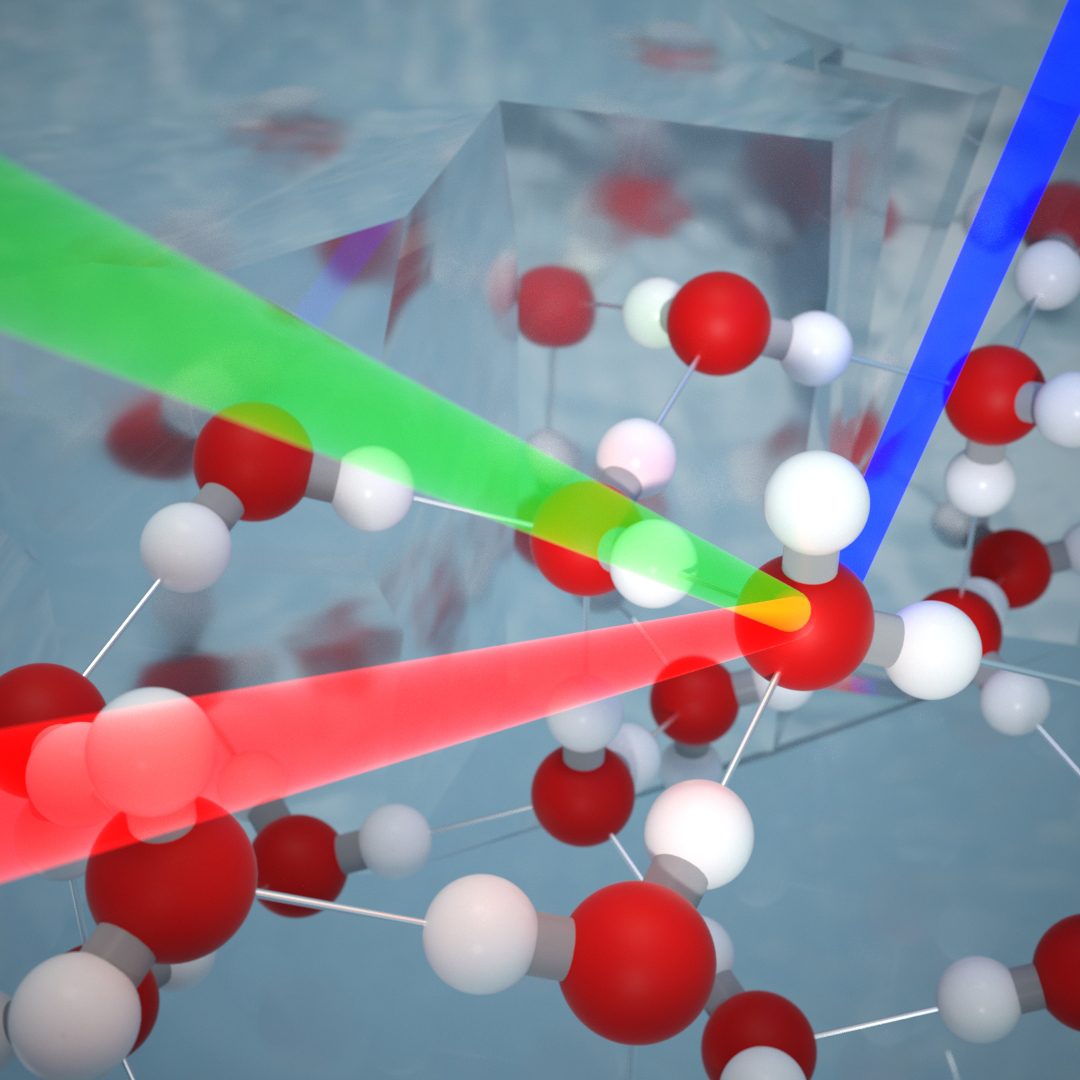

The Dutch researchers used an advanced technique for the research called sum-frequency generation spectroscopy. This technique makes it possible to detect the vibrations of molecules on surfaces by illuminating the surface with two intense femtosecond laser light beams. Under the right conditions, the light beams interact with the molecules on the surface and a light beam with a different color is formed. This only takes place when the beams are reflected on the surface and not on the underlying structure. The color and intensity of the new beam therefore exclusively contain detailed information about the surface structure. With the help of simulations from the Max Planck Institute in Mainz, the researchers were able to translate these results into new knowledge about the ice surface.

Figure 1: Two laser beams interact with molecules on the surface of ice, forming a new beam with a different color. The color and intensity of this laser beam contain detailed information about the molecular structure of the ice surface.

Figure 2: Cross-sections of the surface of ice at different temperatures. The hexagonal structure starts to melt at temperatures below −70 °C, which initially leads to higher density of hydrogen bonds on the ice surface. At −70 °C the maximum number of hydrogen bonds is attained.

Reference

Wilbert J. Smit, Fujie Tang, M. Alejandra Sánchez, Ellen H. G. Backus, Limei Xu, Taisuke Hasegawa, Mischa Bonn, Huib J. Bakker, and Yuki Nagata, Excess Hydrogen Bonding at the Ice–Vapor Interface around 200 K, Physical Review Letters 119, (28.09.17)