Moving massive amounts of CO2 underground: research shows how plant-fungal networks drive nutrient flows that support ecosystems

A study published online in Nature on February 26th has revealed how plants and fungi construct networks that operate as hyper-efficient ‘supply chains,’ moving billions of tons of CO2 underground. By building a robot that tracks over half a million fungal ’roadways’ simultaneously, researchers Tom Shimizu (AMOLF/Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam), Toby Kiers (SPUN/Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam), Howard Stone (Princeton University) and collaborators succeeded in mapping and tracking these nutrient-exchange networks that help regulate Earth’s ecosystems and carbon cycles. With atmospheric CO2 levels rising, the collected data is becoming increasingly important.

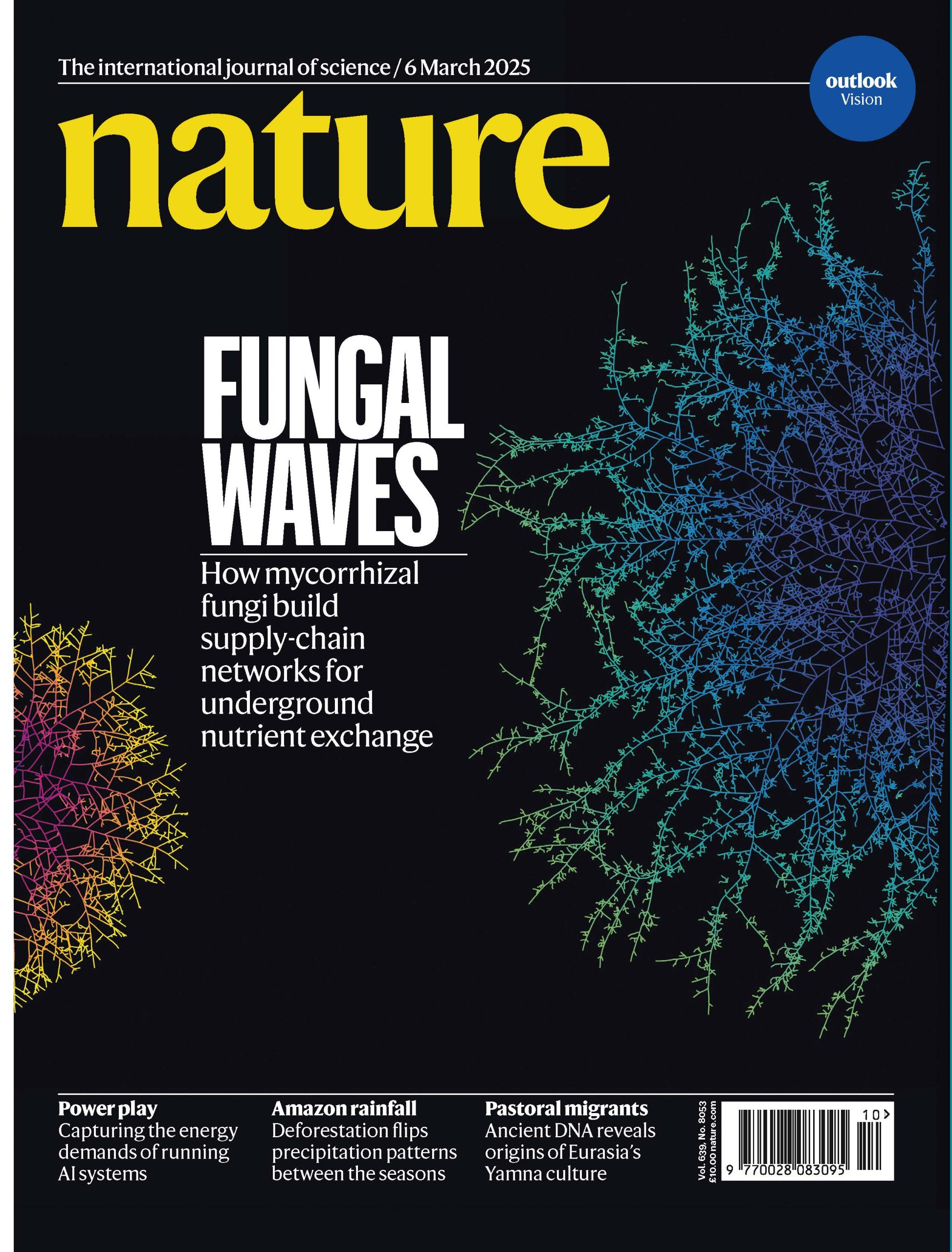

More than 80% of plant species form symbiotic partnerships with mycorrhizal fungi, exchanging carbon for essential nutrients like phosphorus and nitrogen. These networks play a crucial role as entry points of carbon into global soils, drawing down an estimated 13 billion tons of CO2 each year—equivalent to one-third of global energy-related emissions. Despite their importance, scientists had not fully understood how these organisms construct such vast and efficient underground trade routes—until now.

How fungi build and optimize their networks

The international team of 28 researchers discovered that fungi grow in a wave-like pattern, moving carbon outward from plant roots. To support this growth, they manage a system of two-way ‘traffic’, controlling flow speed and the width of the fungal highway based on need.

The researchers also found that fungi send out special microscopic ‘pathfinder’ branches to explore new areas, prioritizing long-term trade potential over short-term growth. This strategic behavior prevents wasteful overbuilding and ensures efficient nutrient exchange between fungi and plants.

Unprecedented precision using robotics

These insights were made possible by a custom-built imaging robot designed and fabricated at AMOLF. The robot tracked the growth of many fungal networks simultaneously over three years, capturing data that would have taken a human researcher a century to collect.

“We’re trying to figure out how these ‘brainless’ microorganisms manage to control their trade behaviors,” says AMOLF group leader Tom Shimizu. “We discovered here that fungi constantly refine their trade routes, adding loops that shorten paths to and from plants and boost efficient nutrient delivery.” Using advanced imaging techniques, researchers at AMOLF obtained and analyzed live footage of nutrient flows throughout the system, resembling two-way traffic on a busy road.

Watch the video showing ‘two-way traffic’ in fungal network or Watch the video in which authors discuss their findings

What fungi can teach us about supply chains

The research highlights how fungi have evolved highly efficient distribution strategies; systems that humans can learn from.

“Humans increasingly rely on AI algorithms to build supply chains that are efficient and resilient. Yet fungi have been solving these problems for more than 450 million years. This is the kind of research that keeps you up at night because these fungi are such important underground circulatory systems for nutrients and carbon,” says Toby Kiers (SPUN/VU).

Implications for climate and carbon storage

With rising atmospheric CO2 levels, understanding fungal networks is more critical than ever. The scientists aim to explore what factors trigger fungi to store more carbon underground, potentially offering new strategies for climate mitigation.

“Understanding how these fungal networks adjust internal flows and resource trading to build supply chains in response to environmental stimuli will be an important direction for future research,” says Howard Stone (Princeton University).

The team is now in the final stages of building a new robot that will increase data collection by a further 10x, allowing them to explore how fungal networks respond to rapid environmental change, including increases in disturbance such as tilling the soil and rising temperatures.

Reference

Loreto Oyarte Galvez, Corentin Bisot, Philippe Bourrianne, Rachael Cargill, Malin Klein, Marije van Son, Jaap van Krugten, Victor Caldas, Thomas Clerc, Kai-Kai Lin, Félix Kahane, Simon van Staalduine, Justin D. Stewart, Victoria Terry, Bianca Turcu, Sander van Otterdijk, Antoine Babu, Marko Kamp, Marco Seynen, Bas Steenbeek, Jan Zomerdijk, Evelina Tutucci, Merlin Sheldrake, Christophe Godin, Vasilis Kokkoris, Howard A. Stone, E. Toby Kiers and Thomas S. Shimizu, A travelling-wave strategy for plant–fungal trade, Nature, February 26, (2025).

Doi: 10.1038/s41586-025-08614-x

Funding and publication

The study, A Travelling-Wave Strategy for Plant–Fungal Trade, was published in Nature and funded by the Human Frontier Science Program (HFSP), Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO), the Grantham Foundation, the Paul Allen Foundation, and the Schmidt Family Foundation.

Contact

Tom Shimizu

e-mail: t.shimizu@amolf.nl