Ice skating on water, even when it is really cold

The outermost layer of ice behaves like liquid water, even at a temperature of –30°C. Physicists at AMOLF have irrefutably demonstrated this using a modern surface-sensitive measuring technique. At lower temperatures, however, the layer of water becomes increasingly thin. The researchers report their findings on 27 November in the journal Angewandte Chemie.

The slipperiness of ice not only ensures that glaciers slide downhill, but also that we can skate on ice, whereas that is not possible on surfaces like concrete or glass. But what makes ice so slippery? One of the reasons is that the outermost layer of ice is more similar to a liquid than a solid. Researchers from Amsterdam have now experimentally demonstrated for the first time that the surface of ice has the same characteristics as liquid water, even at –30°C. This thin layer of water also explains why two ice cubes in the freezer can freeze together when they come into contact, whereas that does not happen for two blocks of wood.

AMOLF researchers Wilbert Smit and Huib Bakker studied the strength of the bonds between water molecules in the top layer of ice. As the surface is very thin, they used a sensitive technique that can visualize the behavior of only the outermost molecules of the surface. That was still a problem during previous research into the surface of ice, as the measuring equipment could not distinguish between the top layer and the rest of the ice.

The two researchers found that the liquid outermost layer became increasingly thin as the temperature dropped: from four molecular layers at –3°C to two molecular layers at –30°C. As the ice is cooled down further, even the outermost layer eventually becomes frozen. That is one of the reasons why ice becomes less slippery at temperatures below –30°C. In those circumstances, ice skating becomes increasingly more difficult.

Sensitive technique

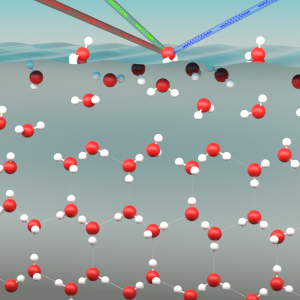

The researchers used an advanced technique called sum-frequency generation spectroscopy. This technique makes it possible to register the behavior of the surface very specifically, without passing on any information about the area underneath. If the surface is illuminated with two intense light beams of very rapid (femtosecond) lasers, then under the right conditions the two light beams only interact with the molecules on the surface. This produces a light beam of a different color. The color and intensity of this beam contain detailed information about the molecular structure of the surface.

By combining two laser beams (illustrated as red and green) on the surface, a new light beam (blue) is produced that contains detailed information about the arrangement of water molecules on the surface of ice. Using this technique, the researchers discovered that the surface of ice behaves in exactly the same way as liquid water, even at a temperature of –30°C.

Reference

Wilbert J. Smit and Huib J. Bakker, The Surface of Ice is Like Supercooled Liquid Water, Angewandte Chemie 56, pp. 15540 –15544, DOI: 10.1002/anie.201707530